Near and Dear: Buildings and Spaces Affect Who We Meet, Work with and Marry

At an MIT Media Lab members meeting about 10 years ago, a colleague, Steven, from member company Cisco challenged the need for a physical workspace. As a maker of telepresence technology, he explained that Cisco’s vision was to eventually make physical space obsolete. I’m reminded of this conversation because the recent pandemic has served as a prolonged experiment in remote work and made us reconsider the role of the physical workplace and in-person meetings. Certainly, some workers have found benefits in remote work: flexibility; the option to live farther from work; respite from the traffic-filled commute; or a quieter place for focus work. Some business owners are considering a partly remote workforce to save on rent or using virtual work to expand their pool of available talent. What are we missing by going remote? It's worth looking at quantitative studies that show how physical space impacts our work and relationships.

We Communicate More with People Nearby

Since the 1970's the late MIT management professor, Tom Allen, and his colleagues have worked to understand how knowledge spreads within organizations and workplaces. In a study (Allen, 1984) conducted over a few months, researchers regularly surveyed engineers and scientists at seven companies, asking them to list colleagues they communicated with about technical matters over the course of the workday.

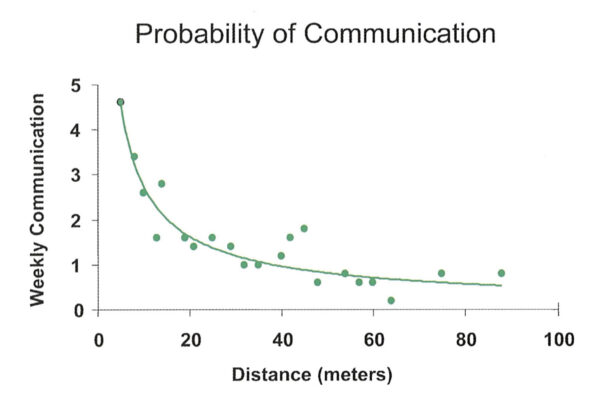

The researchers found that people communicated more often with nearby colleagues. While this finding might seem intuitive, what is surprising is how quickly communication drops off with distance—a function now known as the Allen Curve. A colleague 30 meters away will likely speak with you only once a week.

Nearby colleagues communicate more not solely because they are in the same work group. Even within work groups, communication drops off with distance.

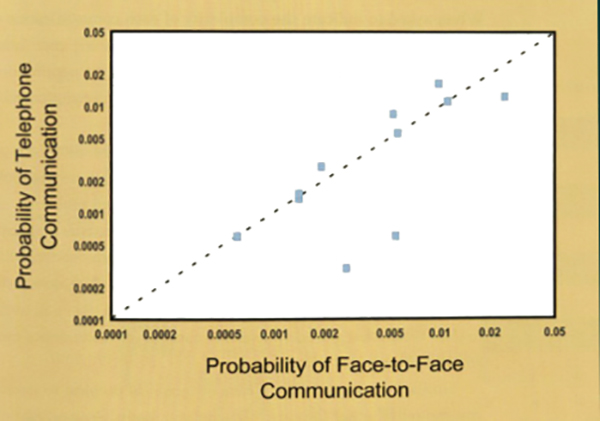

It would make sense for people in an organization to try to communicate more with distant colleagues, but what happens is the opposite. Rather than making up for reduced in-person communication, we actually email and call distant colleagues less frequently.

Allen (1986) explains that communication in a technical organization serves three main purposes:

- Coordination: Organizing different roles in an organization and making people aware of what others are doing.

- Information: Spreading and using existing knowledge.

- Inspiration: Generating new ideas, sometimes from unplanned interactions between people in different groups.

How we locate people in a workplace can impact organizational effectiveness and creativity.

Proximity Influences Social Bonds, Who We Meet and Marry

Proximity also affects our social bonds. Several decades ago, in a study of friendships at MIT’s Westgate married housing dorms, Festinger, Schachter and Back (1950) found that people were more likely to be friends with others in the same building and on the same floor. Students living in high traffic areas — the units in the middle and next to stairs — made more friends than occupants of more remote units.

Even small distances can affect our selection of friends. A study conducted in University of Chicago dorms showed that students were more likely to be friends with the person next door, 8 feet away, than the person two doors down, 16 feet away (Priest and Sawyer, 1967).

Space also fosters our longer-term relationships. Bossard’s (1932) study of marriage licenses in Philadelphia found that residents were more likely to marry people who lived nearby. About one-third of couples who married lived within 5 blocks of each other, and the number of couples getting married dropped off with distance. We might marry people in the same neighborhoods because of common cultural, economic or ethnic backgrounds. So, it’s likely that both proximity and similarity affect our marriage choices.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, living and working patterns will likely change. But these studies remind us that even with remote technologies, the physical workplace, buildings and cities are still critical to our work and social connections.

References

Allen, T. J. (1984). Managing the flow of technology: Technology transfer and the dissemination of technological information within the R&D organization. MIT Press.

Allen, T. J., & Hauptman, O. (1987). The Influence of Communication Technologies on Organizational Structure: A Conceptual Model for Future Research. Communication Research, 14(5), 575–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365087014005007

Allen, T. J. & Henn, Gunter. (2007). The organization and architecture of innovation: Managing the flow of technology. Elsevier.

Bossard, J. H. S. (1932). Residential Propinquity as a Factor in Marriage Selection. American Journal of Sociology, 38(2), 219–224.

Festinger, L. 1919-1989., Schachter, S. 1922-1997., & Back, K. W. (1963). Social pressures in informal groups: A study of human factors in housing. Stanford University Press.

Robert F. Priest & Jack Sawyer. (1967). Proximity and Peership: Bases of Balance in Interpersonal Attraction. American Journal of Sociology, 72(6), 633–649.