What if you knew that working in a windowless office, you might sleep less (about 46 minutes less every night) and that chronic poor light exposure was associated with a host of negative long-term health effects?

A window might seem like a small workplace perk, but some studies underscore the importance of planning workspaces to prioritize healthy light exposure.

A little background: An internal 24-hour biological clock regulates our body systems, including hormones, such as cortisol and melatonin, that regulate when we feel alert or tired. This 24-hour circadian rhythm will cycle even if you’re blind or stuck in a cave. However, light syncs this clock and can reset it if you are exposed to light at an unexpected time. This reset occurs when we travel to a different time zone and spend a few days adjusting to jet lag, waking up early in the middle of the night or feeling prematurely groggy before dinner.

Seasonal change in length of the day can also affect our well-being. Here in Boston, on the winter solstice, sunset arrives at 4:15 p.m. Some people feel less cheery during these short winter days. In addition, sleep quality in the winter actually declines. At the Greenbuild conference in 2015, Mark Rea and Mariana Figueiro reported on studies they had conducted with the General Services Administration (GSA) on workers in Federal buildings. Study participants wore “Daysimeters” to measure how much light they saw throughout the day and activity trackers to measure movement. Compared to the summer, study participants in winter:

- Didn’t sleep as long during winter (about 30 minutes less per night)

- Slept less efficiently, and

- Took about an hour longer to fall asleep every night.

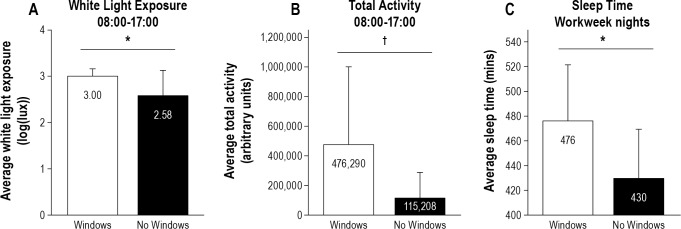

Furthermore, light exposure in our office environments can affect health and well being. Mohamed Boubekri, Ivy Cheung and colleagues found that compared to workers in windowless workspaces, workers near windows (see Figure 1, below):

- Received more light (graph A)

- Were more active during the day and (graph B)

- Slept an average of 46 minutes more every work night compared to their windowless colleagues. (graph C)

By affecting sleep and disrupting our biological clock, poor light exposure also has long-term health effects. Reviewing some of the research literature, Boubekri, Cheung and colleagues note that “[t]here is much evidence that links insufficient sleep and/or reduced sleep quality to a range of significant short-term impairments such as memory loss, slower psychomotor reflexes, and diminished attention. If windowless environments or lack of daylight affect office workers’ sleep quality, there will be subsequent effects not only individually but also on a societal level, leading to more accidents, workplace errors, and decreased productivity. Sleep quality is also an important health indicator that may have effects on, and interactions with mood, cognitive performance, and health outcomes such as diabetes and other illnesses.” (pp. 603-604)

Likewise, Rea and Figueiro list a number of other studies that document the longer-term health effects associated with biological clock disruption:

- “Poor sleep and higher stress (Eismann et al. 2010)

- Increased anxiety and depression (Du-Quiton et al., 2009)

- Increased smoking (Kageyama et al., 2005)

- Cardiovascular disease (Young et al., 2007; Maemura et al., 2007)

- Type 2 diabetes (Kreier et al., 2007)

- Higher incidence of breast cancer (Schernhammer et al., 2001; Hansen, 2006)”

Circadian disruption alone doesn’t cause these diseases. Rather, Rea and Figueiro clarify that people have genetic predispositions towards various illnesses which can be expressed when their environments are unhealthy or stressful.

Like other health habits (e.g., daily exercise, avoiding sweets), the effects of light are, unfortunately, too easy to ignore because they are gradual and cumulative. We spend about 90% of our time indoors, so over the course of years, these small effects add up. That we’re working inside buildings so much also gives us the opportunity to impact health on a daily basis by incorporating research into design.

Bibliography: